On 13 March 1775 the Moroccan diplomat Aḥmed al-Ghazzāl (d. 1777) sent an urgent letter to his Spanish counterpart, the Marqués de Grimaldi (i.e. Jerónimo Grimaldi, d. 1789). In his letter al-Ghazzāl attempts to temper growing animosities between the two states and, in doing so, clear up a potentially disastrous misunderstanding. To quell tempers and reassure the marqués, the Moroccan diplomat writes:

The actual attack was not a result of a defect of the heart or even greed, but rather that which was dictated by our religion. For you will not find our prince, may God make him victorious, neglecting his preservation of the religion just as you preserve your own religion …. And so, in reality it is the ministers who are responsible for that which occurs between kings. If there is goodness they are extolled for it. If there is evil they fix it and are blamed for it. For kings do not emit anything but good. And the attainment of this [order], either good or otherwise, is the responsibility of the ministers. [This is because] the state of affairs is fleeting and in every instance it returns to that which is best. So mull that over in your mind and, in turn, respond to that which I wrote to you. (MWM 11890110-A12-002-001)

Al-Ghazzāl’s explanation places enormous onus on ministers and diplomats in sustaining international affairs. For al-Ghazzāl these are the individuals responsible for ensuring worldy order, peace, and understanding. In placing this emphasis on the diplomat, al-Ghazzāl’s reasoning touches on one of the more elusive aspects of Moroccan diplomatic history in the eighteenth century. His assertion urges us to reconsider whether the story of Moroccan diplomacy is one centered on the authority and power of the king, Sīdī Muḥammad bin ʿAbd Allāh (Muḥammad III, r. 1757-1790) or, like al-Ghazzāl suggests, one where the diplomats and ambassadors play a more prominent role.

From various archives, we know that Moroccan diplomats were particularly active during this time period, traversing the middle sea to sign peace treaties and confirm trade agreements. Nevertheless, more often than not, this activity is attributed to the policies and persona of Muḥammad III. On an international scale, the Moroccan sovereign is well-known for signing over a dozen peace and commerce treaties with European counterparts, overseeing European consular activity in Morocco, and establishing the Atlantic port city of Essaouira. As a result of these developments, the history of Moroccan diplomacy largely centers around the figure of the king. Contrarily, when individual diplomats appear, they are often portrayed as ad hoc ambassadors, with little past, present, or future connections to court policy.

Yet, al-Ghazzāl’s statement infers a more complicated story. Was this just a boastful attempt to garner favor and recognition from his Spanish counterpart? Or does al-Ghazzāl’s assertion help us to better nuance the developments of eighteenth-century Moroccan diplomacy? As a way to interrogate al-Ghazzāl’s statement, this post presents a brief introduction to network analysis, run through the program Cytoscape. Since network analysis allows us to examine actors in relation to others, we can use it to begin to paint a more connected picture of Moroccan diplomacy. Based on a few examples from my dissertation - “Divinely Guided Ambassadors: Ottoman and Moroccan Roots of Modern Diplomacy in the Eighteenth-Century Mediterranean” - I hope that this brief introduction may urge others to explore how Digital Humanities tools can complement textual sources to help us ask new questions and write more plural histories.

There is one final nota bene before we start. While documents for diplomacy can be found all across the Mediterranean, this analysis focuses on those diplomatic correspondence that are currently housed in the Mudīriyya al-Wathā’iq al-Malakiyya (Archive of Royal Documents, henceforth: MWM) in Rabat, Morocco. In particular, this network analysis is based on letters sent by Moroccan actors, with note of the recipient, their state affiliation, and the date the letter was sent.

With that, let’s look at some graphs in order to highlight a few of the analytical features of Cytoscape when applied to a network analysis of Moroccan diplomatic correspondence.

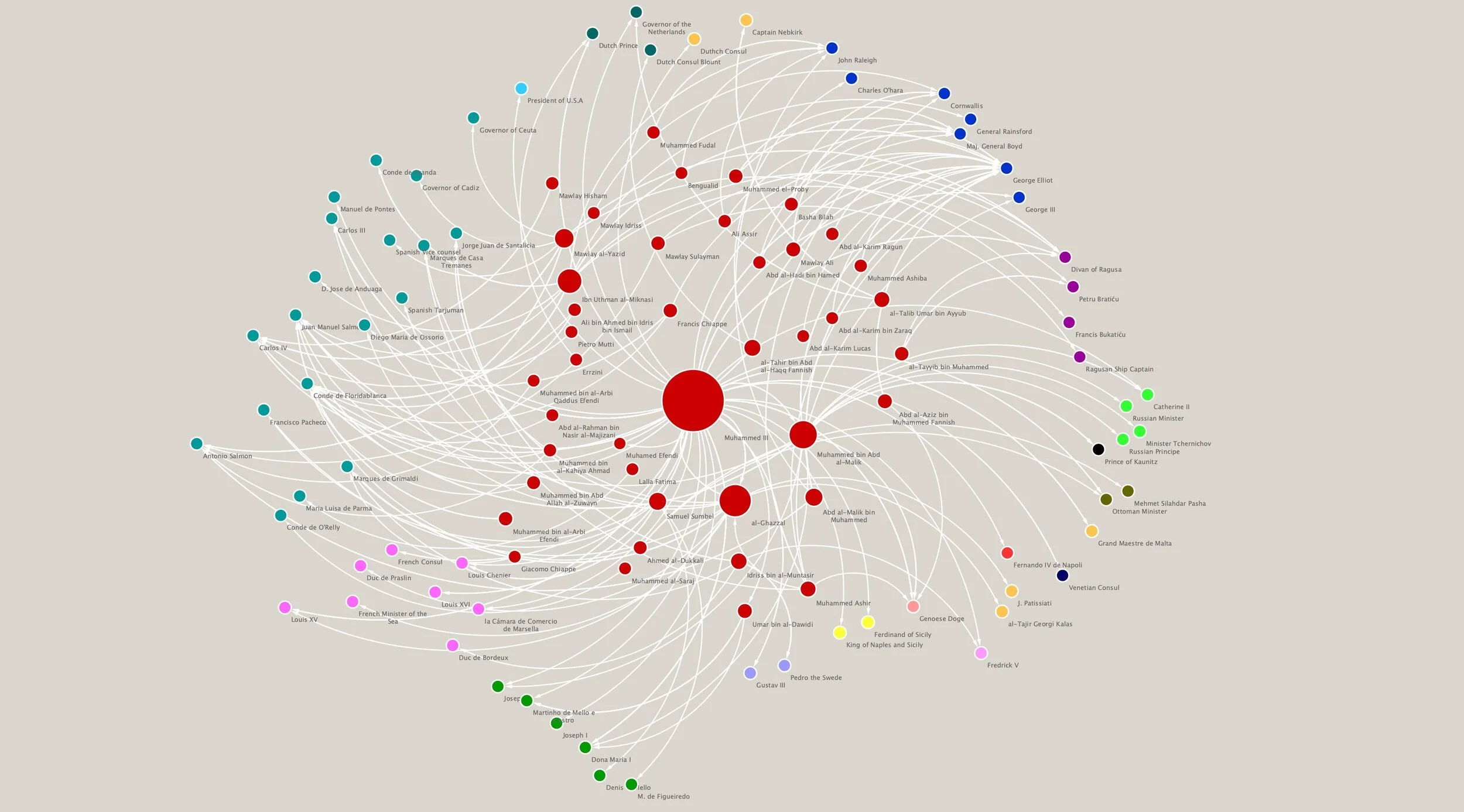

Network of Moroccan diplomatic correspondence circa 1757 - 1792.

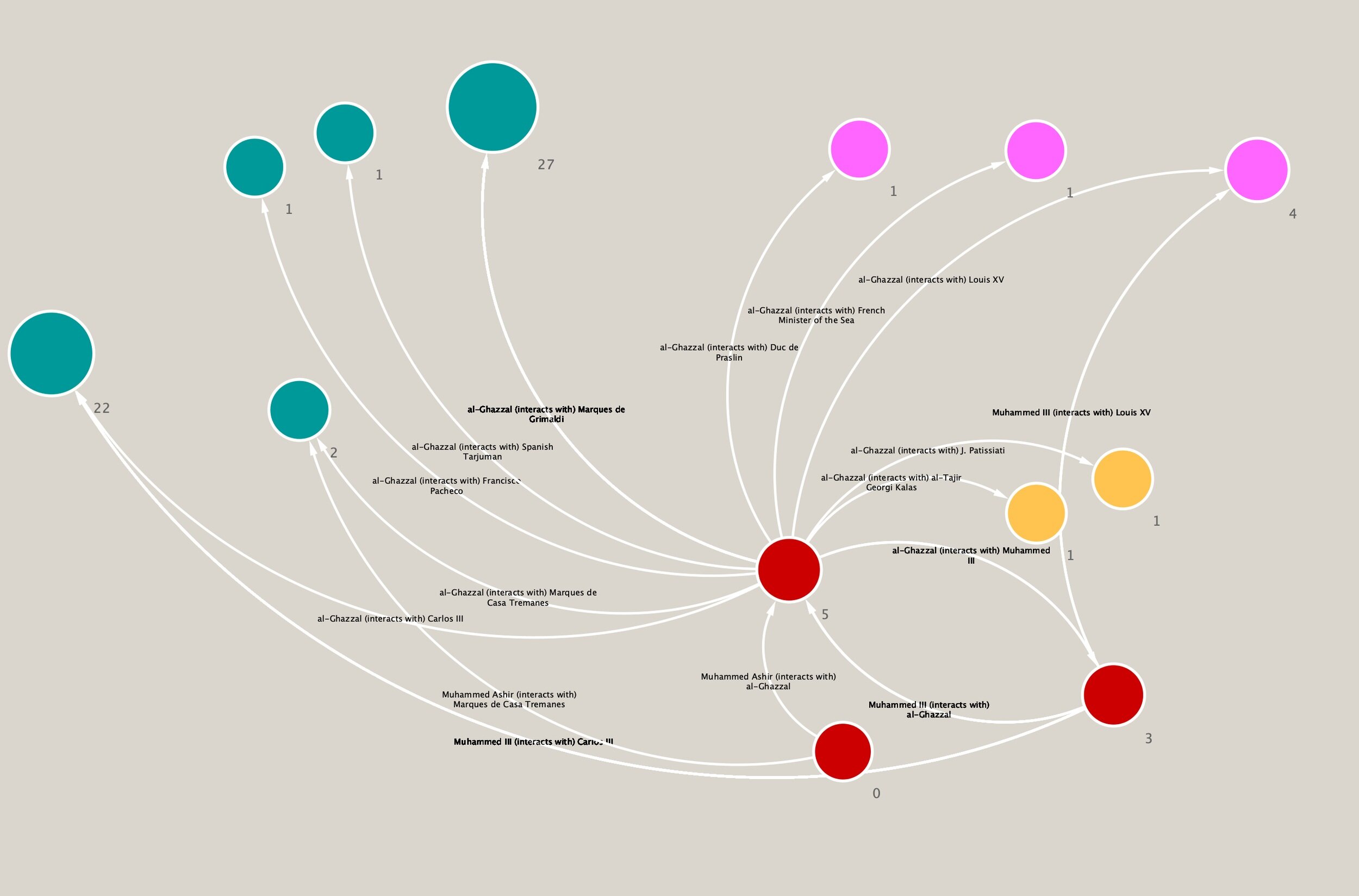

Above is a graph of the diplomatic correspondence from the MWM. I have programed this to be analyzed through Cytoscape to highlight a few important elements. First, each node (circle) represents an individual. These individuals are identified by the text displayed next to them. For instance, if we zoom in, we can see figures differentiated by various colors (Red = Morocco, Aqua = Spain, Neon Blue = U.S.A., Dark Turquoise = Dutch). Their names or titles (if a name is not specified) further identity each node.

Another feature of this graph is the various sizes of the nodes. This comes from an analytical function of Cytoscape that allows one to indicate relative output. You will notice that in the graph, only the ‘Red’ / Moroccan nodes change in size. This is because the data set is defined by letters sent by Moroccans. As a result, the output can only come from Moroccan nodes. Let’s zoom in on the center of the graph to see what this means.

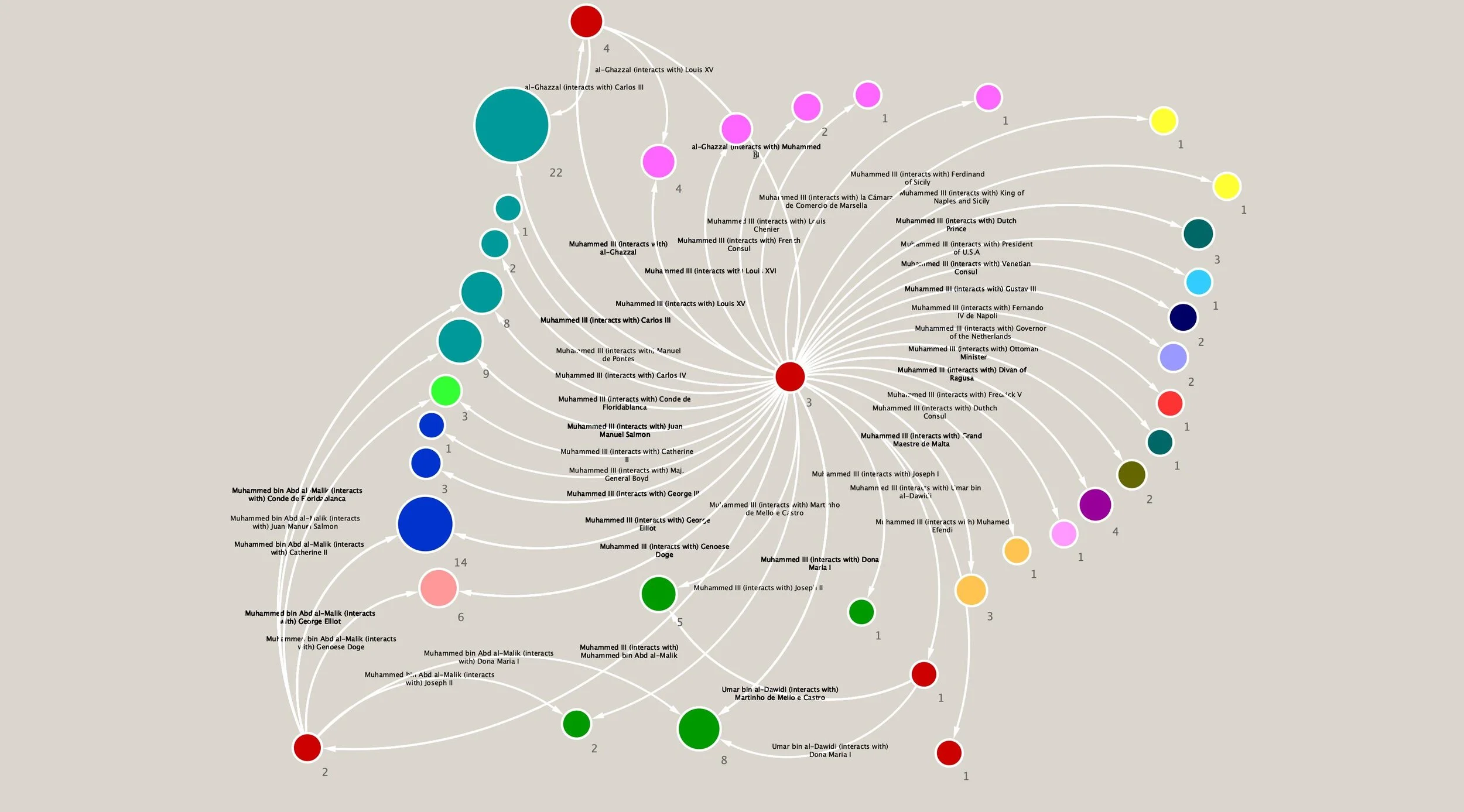

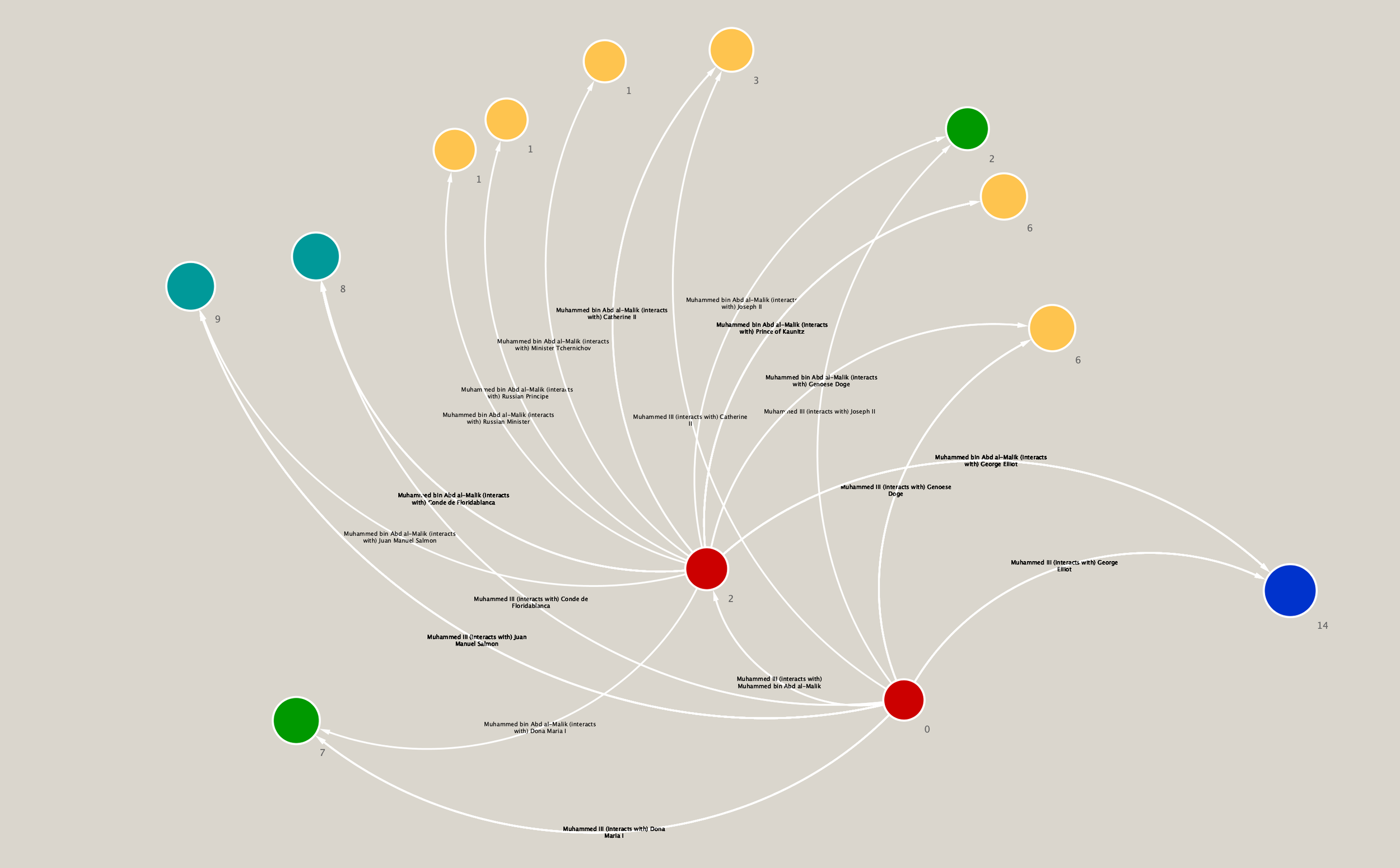

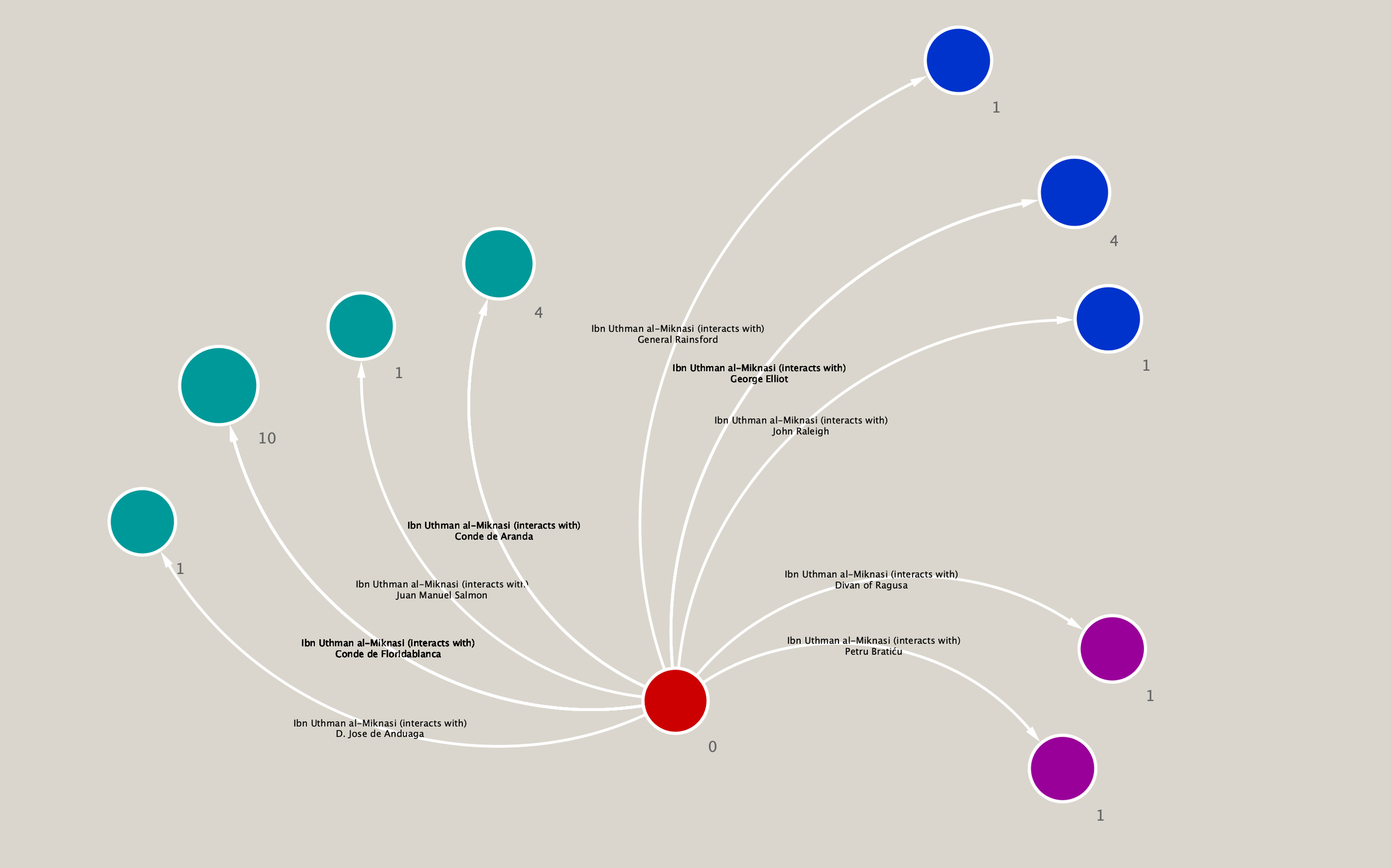

As you can see above, the size of the Moroccan nodes varies considerably. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the largest node is that of Muḥammad III, king of Morocco. In addition, the nodes of Ibn Uthmān al-Miknāsī, al-Ghazzāl, and Muḥammad bin ʿAbd al-Mālik are all larger than their peers. This means these actors sent more letters than the other Moroccans featured on the graph. But what does their output actually look like? Why is Muḥammad III’s node so big? Here, Cytoscape allows us to isolate nodes of the network and run new analyses based on individual parts of the larger network. For instance, in the graph below I isolated Muḥammad III’s node and ran an analysis of input vis-à-vis his connections. (i.e. the number of correspondence received by Muḥammad III’s counterparts.)

Graph of Muḥammad III’s connection indicating the number of letters received by his counterparts

Muḥammad III is at the center, but his node is small because we are calculating how many letters were received from him. The nodes around him represent mostly non-Moroccan counterparts. The larger their node, the more letters they received from Muḥammad III. A closer look will help to clarify and point out some labelling features of Cytoscape.

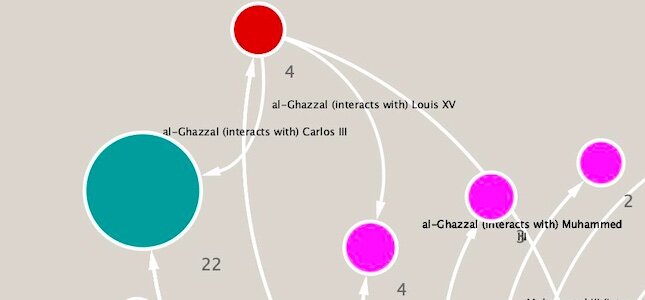

Zoom in on Muḥammad III’s interactions with Spanish, British, and Russians.

From this perspective we can see that Cytoscape, in addition to displaying relative node size, labels the number of incoming letters. Moreover, it labels the interaction, noting that Muḥammad III ‘interacts with’ his various counterparts. In the image on the left, we have a selection of Spanish, British, and Russian counterparts.

As we notice from this zoomed-in version, Muḥammad III had a wide array of connections. Several of these were relatively strong, meaning he sent multiple letters to them. However, a majority of these interactions are defined by less than four letters. Over a thirty-year reign four letters does not amount to much communication. Furthermore, the sovereign’s most heightened interactions are with Morocco’s closest neighbors: the British in Gibraltar, the Spanish, and the Portuguese. As we can see from this graph (zoom-in below), some of the input for the British, Spanish, and Portuguese relationships also comes from the Moroccan diplomats al-Ghazzāl and Muḥammad bin ʿAbd al-Mālik.

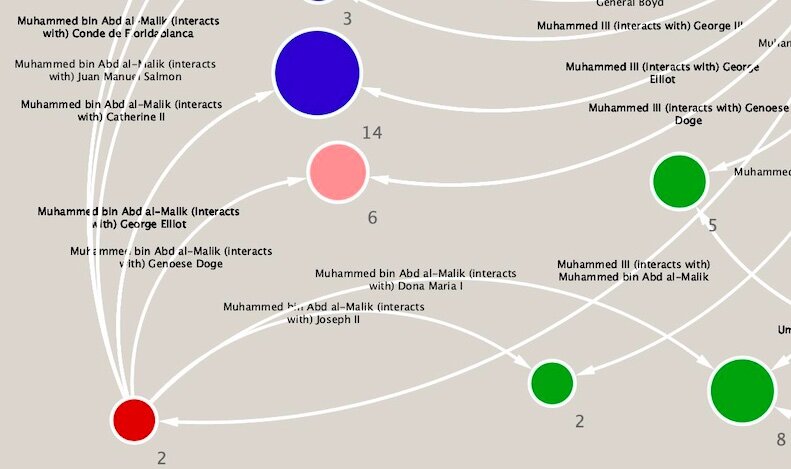

Thus, while Muḥammad III had heightened interactions with a few primary counterparts, the relative size of his node in the main graph is also caused by a large number of much less intense relations with characters like Fernando IV in Napoli or the U.S. President, George Washington. Furthermore, his relations with the primary counterparts are shared by several of his diplomats. This more intimate view of Muḥammad III’s relations is the first clue that al-Ghazzāl’s statement may be more than just a boastful claim to his Spanish counterpart. To further explore this theory, let’s take a closer look at the individual graphs of the three most prominent diplomats, according to this network.

By separating out these diplomats, we can identify a few aspects of their graphs that indicate a Moroccan diplomatic system similar to that which al-Ghazzāl describes - one where the diplomat takes on an active role in creating and sustaining relations between kings. That is, the individual graphs offer a glimpse of a system that may not have been entirely dominated by the decisions, actions, and authority of Muḥammad III.

The first feature of these graphs we can highlight is the intensity of the relations that the Moroccan diplomats had with their respective counterparts. Al-Ghazzāl sustained intensive relations with the Marqués de Grimaldi, sending him 27 letters. Muḥammad bin ʿAbd al-Mālik sustained relations with Juán Manuel Salmón, the Conde de Floridablanca, Prince Kauntiz of the Habsburgs in Vienna, and George Elliot of the British in Gibraltar, sending 9,8, 6, and 13 letters, respectively. Similarly, al-Miknāsī sent 10 letters to Conde de Floridablanca and 4 to George Elliot. This level of intensity - usually confined to ten year periods - suggests that these diplomats had continued relations with their counterparts before, during, and after their missions. This was not just ad hoc diplomacy, but something more specialized where individuals sustained relations with particular counterparts over extended periods of time.

A second characteristic of these relations that the network analysis highlights is the timeline of the individual ambassador’s relations. As the key to the graphs indicates, there is very little overlap between the individual Moroccan diplomats and their peers. Al-Ghazzāl’s letters span the time period from 1766-1776, Muḥammad bin ʿAbd al-Mālik's range from 1777-1787, and al-Minkāsī’s span 1783-1795. Like the intense relations with specific counterparts, this lack of substantial overlap again points toward a specialization where single diplomats are assigned to deal with particular foreign powers and affairs during a set period of time. While there is no indication that there was a formalized system of diplomatic tenures or formal titles, the graphs suggest that something similar existed in practice. Most importantly, both of these characteristics suggest a system in which the diplomat had a certain degree of creative power and ability, as asserted by al-Ghazzāl.

With a focus on one archive, these graphs do not present a definitive conclusion about the features of the Moroccan diplomatic system in the eighteenth century. For example, a fairly active diplomat, al-Ṭāhir Fannīsh, is barely represented by the documents in al-Mudūriyya al-Wathā’iq al-Malakiyya. Nevertheless, this type of analysis offers a first glimpse into the relationship between how diplomats perceived themselves, as documented in their correspondence, and the reality of the situation on the ground. Continuing to build up this kind of database with correspondence from additional archives will help to develop a more nuanced image of the Moroccan diplomatic system, its various characters, the subjectivity of individual diplomats, and, ultimately, their impact on diplomatic practices and policies across the Mediterranean.

Resources and Bibliography

Archives

Dubrovnik, Croatia, Dubrovnik State Archives: Acta Turcarum, Diplomata et Acta, Lettere e Commissioni.

Gibraltar, U.K., Gibraltar Government Archives, U.K.: Barbary 1776, Letters to Tetuan and Tangier.

Rabat, Morocco, Mudīriyya al-Wathā’iq al-Malakiyya, Eighteenth Century Folders.

Resources on Cytoscape and DH

Liu, Alan “The State of Digital Humanities: A Report and a Critique.” Arts and Humanities in Higher Education, 11.1-2 (2012): 8-41.

Miriam Posner has an excellent introduction to Cytoscape here: https://miriamposner.com/blog/tag/cytoscape/

Miriam Posner “What’s Next: The Radical, Unrealized Potential of Digital Humanities” Debates in Digital Humanities 2016.

Weingart, Scott “Demystifying Networks, Parts I & II.” Journal of Digital Humanities, 1 (2011): http://journalofdigitalhumanities.org/1-1/demystifying-networks-by-scott-weingart/

Resources on Moroccan Diplomacy

Alloul, Houssine, and Michael Auwers. 2018. “What Is (New in) New Diplomatic History?” Journal of Belgian History XLVIII (4): 112–22.

Bsoul, Labeeb Ahmed. 2007. “Theory of International Relations in Islam.” Digest of Middle East Studies 16 (2): 71–96.

Caillé, Jacques. 1960. Les Accords Internationaux Du Sultan Sidi Mohammed Ben ʿAbdallah (1757-1790). Paris: Librarie générale de doit et de jurisprudence.

Côté, Marie-Hélène. 2010. “What Did It Mean to Be a French Diplomat in the 17th and Early 18th Centuries?” Canadian Journal of History XLV: 235–58.

al-Ghazzāl, Aḥmad. 2017. The Fruits of the Struggle in Diplomacy and War: Moroccan Ambassador al-Ghazzal and His Diplomatic Retinue in Eighteenth-Century Andalusia. Edited by Travis Landry. Translated by Abdulrahman al-Ruwaishan. Lewisburg, PA: Bucknell University Press.

al-Ghazzāl, Aḥmad. 2012. Natījat Al-Ijtihād Fī al-Muhādanah Wa-al-Jihād. Edited by Ismāʿīl al-ʿArabī. Tunis: Dār al-Gharb al-Islāmī.

Ibn al-Farrāʼ, al-Ḥusayn ibn Muḥammad, and Maria Vaiou. 2019. Diplomacy in the early Islamic world: a tenth-century treatise on Arab-Byzantine relations : The book of messengers of Kings (Kitāb Rusul al-Mulūk) of Ibn al-Farrā’.

Ibn ʿAbdallāh, ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz. 1985. Al-Safāra Wa-l-Sufarā’ Bi-l-Maghrib ʿabra al-Tārīkh. Rabat: al-Maʿhud al-Waṭanī li-l-dirāsāt.

Ibn Zaydān, ʻAbd al-Raḥmân, and ʻAbd al-Wahhāb Binmanṣūr. 1962. al-ʿIzz wa al-ṣawla fi maʿālim niẓām al-dawlat. Rabat: al-Maṭbaʿat al-Malikiyya.

Lourido Díaz, Ramón. 1989. Marruecos y el mundo exterior en la segunda mitad del siglo XVIII: Relaciones politico-comerciales del sultan Sīdī Muḥammad b. ʿAbd Allāh (1757-1790) con el exterior. Madrid: Dispograf.

Matar, N. I. 2015. An Arab Ambassador in the Mediterranean World: The Travels of Muḥammad Ibn ʻUthman al-Miknasi. New York: Routledge.

Māgāmān, Muḥammad. 2014. Al-Riḥlāt al-Maghribiyya Fī al-Qarnayn al-Ḥādī ʿashr Wa al-Thānī ʿashr Lil-Hijra al-Muqāfiq Lil-Qarnay al-Sābiʿ ʿashr Wa al-Thāmin ʿashr Lil-Mīlād. Rabat: Jāmiʻat Muḥammad V.

al-Miknāsī, Muḥammad ibn ʻUthmān. 1965. Al-Iksīr Fī Fikāk al-Asīr. Edited by Muḥammad Fāsī. Rabat: Jāmiʻat Muḥammad V.

Qaddūrī, ʻAbd al-Majīd. 2003. al-Tārīk̲h wa-al-diblūmāsiyya: qaḍāyā al-muṣṭalaḥ wa-al-manhaj. Rabat: Jāmiʻat Muḥammad V.

Qaddūrī, ʻAbd al-Majīd. 1995. Sufarā’ Maghāriba Fī Urubbā, 1610-1922. Rabat: Jāmiʻat Muḥammad V.

Roberts, Priscilla H., and James N. Tull. 1999. “Moroccan Sultan Sidi Muhammad Ibn Abdallah’s Diplomatic Initiatives toward the United States, 1777-1786.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 143 (2): 233–65.

al-Tāzī, ʻAbd al-Hādī. 1988. Al-Tārīkh al-Diblūmāsī Lil-Maghrib: Min Aqdam al-ʻuṣūr Ilá al-Yawm. Vol. 9. 11 vols. Muḥammediyya, Morocco: Maṭbāʿ Faẓāla.

Windler, Christian. 2002. La Diplomatie comme expérience de l’autre: consuls français au Maghreb (1700-1840). Genève: Droz.